Doctor Who was always experimental in the technology it used. Less often acknowledged are the series’ experiments in form. These are particularly notable in the first few years of the series, around which time the wider world of BBC television drama was similarly experimenting.

Perhaps ‘experiments in form’, the modern term for such practices, sounds a touch too academic. A common label at the time to describe this approach was ‘non-naturalism’ although I’m not sure if that’s much better but let’s go with it. Before we can talk about non-naturalism we have to define ‘naturalism’, the dominant style of television drama. There was never one set definition in the context of television, and it was always a much-debated term, but the following covers many of its important features.

Naturalism was the apparently objective representation of staged action, with the viewer given the perspective of a well-placed fly-on-the-wall. It isn’t quite ‘realistic’ however. It is tidier than that. Editing shows the viewer what they need to see and omits the rest. Characters do not cough and splutter or visit the toilet, for example, unless the plot requires them to do so. Naturalism attempts to draw attention away from its artificiality, following set staging and editing conventions that encourage the viewer’s immersion into the story and empathy with the lives of the characters they are being shown.

Given its fantastical concepts and sometimes unconvincing sets or special effects, it may seem odd to suggest Doctor Who was ‘naturalistic’, but by and large it was, following the same conventions as other drama. Any artificiality was (usually) an accidental by-product of the types of stories told and the technology available to realise them, not a deliberate storytelling technique in itself.

The use of more expressionistic methods of presenting the story, often ways which draw attention to, rather than away from, the artificial nature of the production, can be referred to as ‘non-naturalism’. This may involve narratives that do not progress in a linear fashion – condensing or extending story time, or playing tricks with chronology – or techniques which directly address the viewer, divorce sound from vision, or privilege the visual image over television drama’s traditional reliance on dialogue.

Innovation in this manner of storytelling is something Doctor Who’s original associate producer Mervyn Pinfield had helped pioneer as part of the BBC’s Drama Experimental Group (more commonly known as the ‘Langham Group’), at the end of the 1950s. Other, younger, practitioners, such as writers Troy Kennedy Martin and John McGrath, and producer James MacTaggart, came to advocate further new ways of presenting non-naturalistic drama in the early to mid-1960s.

The BBC anthology series Storyboard, Studio 4 and Teletale, seen over 1960-62 and all produced by MacTaggart, specialised in non-naturalistic drama, attempting to tell stories in unusual visual ways, such as by eliminating sets or through the use of montage and rapid vision mixing. Some of the same production personnel continued this experimentation to greater or lesser extents in more mainstream drama, such as on The Wednesday Play, in the mid-1960s. For more on these programmes, see my overview of MacTaggart’s career here.

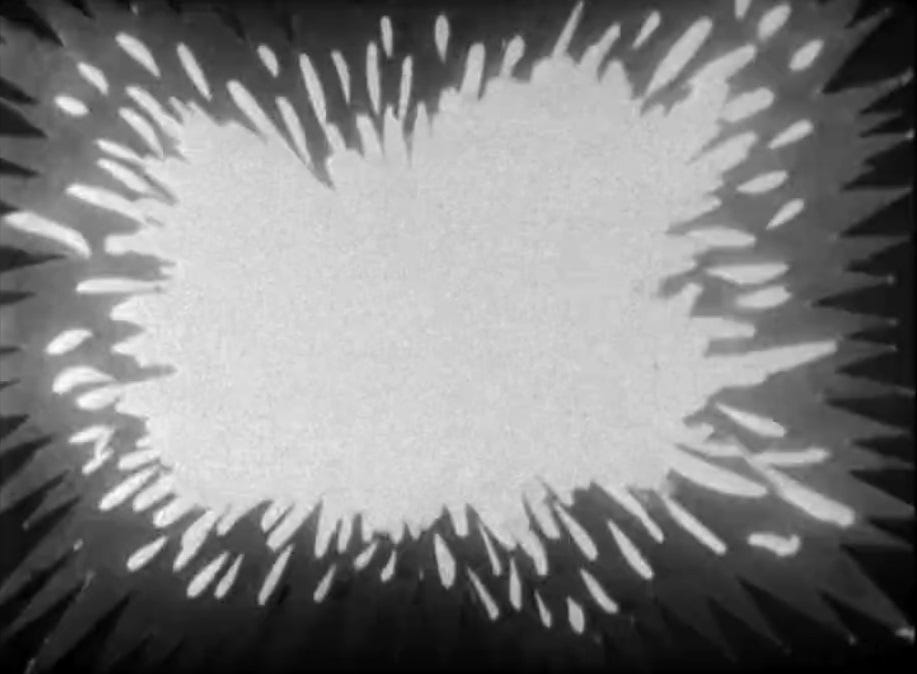

Doctor Who of the same period also dabbled with non-naturalistic techniques, albeit only briefly and occasionally. Although not intended for non-naturalistic purposes, the use of the howl-round titles footage within the very first episode, An Unearthly Child, to illustrate movement through time is an early, if minor, instance of abstract imagery being employed without any direct meaning. Blobby, swirly graphics came to represent the time vortex in later years, but at this early point the howl-round footage is simply a striking piece of imagery. It helps to illustrate the weirdness of the narrative twist but is not an attempt at any sort of literal representation.

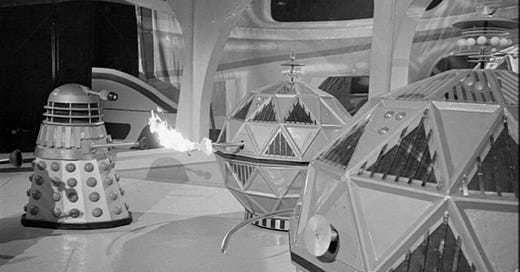

The Planet of Decision, the final episode of 1965’s The Chase, gives us two better examples of non-naturalistic techniques. The battle of the Daleks and the Mechonoids is achieved via a film montage which includes rapid cutting and layered images, which condenses narrative time. Most notably, it uses superimposed animated explosions, creating a cartoonish quality and hinting at a level of destruction that could not be realised on screen. It’s not quite Batman (which brough its ‘Bam!’ and ‘Pow!’ captions to the screen the following year) but it’s heading in that direction. How far this was a deliberate attempt to supersede the series’ usual naturalism is unclear. Director Richard Martin later stated on the story’s DVD that he regretted using some of the cartoon explosions.

The episode’s better example is the late sequence, directed by Douglas Camfield, of Ian and Barbara larking about in London executed as a series of still images. The montage of stills collapses time but illustrates place and mood, depicting in just a few seconds the duo’s joyful first hours back on Earth without any of the potential longueurs (or dialogue) of live action. This was much like the impressive use of the same technique in the experimental non-naturalistic serial Diary of a Young Man (MacTaggart producing again, with directors Kenneth Loach and Peter Duguid) nine months earlier. The serial also employed a rapid montage of stills to illustrate the progress around London of its two protagonists, amongst other uses.

Perhaps the most extreme example of non-naturalistic storytelling in Doctor Who is the playfulness of The Feast of Steven (episode seven of The Daleks’ Master Plan), again directed by Douglas Camfield, from the end of 1965. Most obviously there’s the Doctor’s famous concluding address to the viewer at home. This smashes the naturalistic convention of the ‘fourth wall’ which separates the viewer from the action on screen, thus drawing attention to – and openly acknowledging – the artificiality of the programme. However, more interesting are the earlier sequences set in Hollywood, with their silent cinema-style intertitles. These captions progress the narrative and reflect the setting of this part of the episode. Again, they playfully draw the viewer’s attention to the manner of the programme’s construction.

Director Don Taylor – the man originally offered producership of Doctor Who – had done something similar in directing Hugh Whitemore’s Dan, Dan the Charity Man for The Wednesday Play, broadcast earlier the same year. Like The Feast of Steven, this play is now long lost but contemporary accounts reported how this comedy about advertising was told with unusual dramatic devices such as speeded up film sequences, silent film-style captions and characters pausing the action to address the viewer. The similarities with The Feast of Steven are obvious.

It’s interesting to note how stylistic innovations in Doctor Who seem to follow hard on the heels of similar experiments in the wider output of the BBC drama department. There may be an element of direct imitation, or at least of inspiration being taken, but just as likely this reflects the atmosphere of drama production being one of creative imagination, attuned to the more unusual possibilities of the medium. It’s also notable that, in the period covered here, live transmission for television drama had only recently been phased out (with lingering exceptions), enabling the introduction of new techniques that in many cases required pre-recording.

BBC head of drama (and Doctor Who’s begetter) Sydney Newman had himself advocated “a new kind of dramatic communication” free of “naturalistic trappings” in the Spring 1964 issue of the Journal of the Society for Film and Television Arts. Hopefully he approved of Doctor Who dipping a tentative toe into these waters.

Such experimentation with narrative form continued in wider television drama into the 1980s, in ever more marginalised programmes, but were largely lost to Doctor Who. In common with most mainstream drama, the series increasingly stuck to conventional naturalistic production styles, albeit enlivened by the regular flights of fancy that made it such compelling viewing.

Images © BBC

Sources

Days of Vision, the memoir of Don Taylor (Methuen Drama)

Experimental British Television, edited by Laura Mulvey and Jamie Sexton (Manchester University Press)

The Thrill of the Chase featurette on the BBC DVD: Doctor Who: The Chase

Thank you, interesting article; food for thought.

Thanks for this interesting piece. I occasionally find myself leaping to the defence of Richard Martin for his efforts if not the results.