Forty-five years ago today two titans of 1970s television came together: Doctor Who and John Cleese.

Tom Baker was in his fifth full year as the Doctor and was the well-recognised face of the series across the UK. Cleese was also a household name, but for comedy. He had started to build his comedy reputation in the late 1960s and solidified this with his work on the first three series of Monty Python’s Flying Circus between 1969 and 1973 before ascending to comedy royalty with Fawlty Towers, which he created with his then-wife Connie Booth. Fawlty Towers’ first series was screened in 1975 and the second in 1979, with the final episode going out just after Cleese’s Doctor Who appearance.

Also cameoing with Cleese was actor and comedian Eleanor Bron. She had been in such films as the Beatles’ Help! (1965), and Alfie (1966) alongside Michael Caine, and since the mid-1960s had, like Cleese, become a well-known face on television with roles in a variety of comedy series. She would later return to Doctor Who in 1985 as the villainous Kara in Revelation of the Daleks.

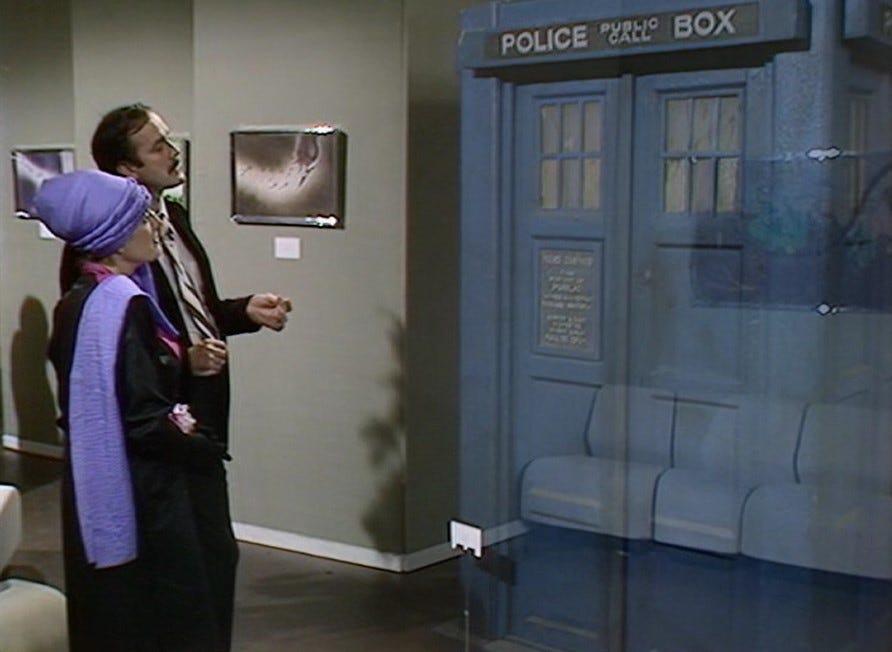

In part four of City of Death, the Doctor, Romana and their new friend Duggan are in desperate need to get to the TARDIS to pursue the villainous Scaroth back in time. The location is contemporary Paris. They run hell for leather across the city, regaining the TARDIS where it was left in the Denise Rene gallery of abstract and modern art. In the moments before their arrival in the gallery, a pair of visitors (Cleese and Bron) are admiring the TARDIS, which they take to be another exhibit.

Cleese: For me, one of the most curious things about this piece is its wonderful afunctionalism.

Bron: Yes, I see what you mean. Divorced from its function and seen purely as a piece of art, its structure of line and colour is curiously counterpointed by the redundant vestiges of its function.

Cleese: And since it has no call to be here, the art lies in the fact that it is here.

At this moment, the Doctor, Romana and Duggan dash into the TARDIS and it promptly dematerialises. The brief scene ends with Bron’s character’s admiration: “Exquisite. Absolutely exquisite.”

The script of City of Death was written apparently by one ‘David Agnew’. This was actually a pseudonym disguising a top to bottom rewrite by the series’ script editor Douglas Adams of the original script by David Fisher. Adams’s background was primarily in comedy, with contributions to a number of radio series and the later episodes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus (and related projects), amongst others. At this point in his career, his star was on the ascendant; his comedy radio serial The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy had enjoyed extraordinary success the previous year and he was working on a book version alongside his Doctor Who duties. He was a man very much in demand. Whilst City of Death’s plotting sometimes betrays its rushed writing, the dialogue sparkles with the humour and wit of Adams at his peak, as exemplified by the Cleese/Bron scene.

The scene is a joke about the (sometimes) pretentiousness of art appreciation. At the risk of being pretentious myself, the dialogue could – at a push –be argued to make a vague sense as a criticism of the TARDIS: it appears to be a redundant and afunctional London police box, but is nevertheless a nice bit of design. Yet, in the female critic’s estimation, the ‘artwork’ becomes “exquisite” only when it ceases to be present. In his Doctor Who Magazine (DWM) feature on City of Death, Alan Barnes points out that when the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre in 1911: “crowds would gather simply to look at the empty space where it once hung.” Intentional or not, it’s a nice similarity. The scene also reflects with comedy the theme of the story, established at the start with the Doctor’s dismissal of computer drawing, and raised at the end with the suggestion that the ‘real’ Mona Lisa has “this is a fake” written on its canvas in felt-tip pen, of what constitutes or disqualifies art. The scene’s a quick joke, but a clever and thematically relevant one.

Adams had wanted the joke to be established earlier in the part two scene in which the Doctor sneaks into the gallery at night to access the TARDIS. In an interview published in DWM in 2002, after his death, Adams explained: “The way that shot was meant to go was that [the viewer] starts off by seeing one exhibit after another and sort of wondering why he’s there, until you get to the sixth or seventh exhibit and it’s the TARDIS!” In recording, this build up to the later Cleese/Bron scene is largely lost. “The thing I liked was the notion of the Doctor, having arrived in Paris and looking for somewhere to hide the TARDIS, parks it in a modern art gallery where he hopes no-one will notice it,” Adams explained.

The scene appears in the original script with the pair of gallery visitors described only as “two Englishmen”. It was director Michael Hayes’s idea to make these instead a man and a woman and to have them played by Cleese and Bron. He recalled in an interview with DWM in 1995: “I knew that John and Eleanor were both mates of Douglas [Adams] and it just swam into my mind, I suppose, that it would be marvellous to have them. I said, ‘Do you think we could possibly…?’ and it was arranged entirely through Douglas. I think they were going to be doing something in another studio more or less at the same time, and they finally agreed to do it, provided it was just a one-off thing with no advance publicity or credit in Radio Times.”

However, possibly even before Hayes’ suggestion, Adams had attempted to interest Cleese in a Doctor Who role of some sort in a casual conversation. The story’s production file includes his letter to Cleese dated 25 April 1979 in which he recalls:

“When we last met over lunch in the rehearsal rooms you were rash enough to say that in principle you’d be happy to consider doing something for us on Doctor Who. Knowing how mind bogglingly busy you are I wondered if you’d actually have the time if it came down to it. However, if you really are willing in principle there is a one-scene cameo part which would take no time at all and would be great fun if you were able to do it.”

He went on to outline the scene and suggest that if Cleese would play one of the critics, “we might see if we could get someone like [humourist and broadcaster] Alan Coren to do the other.” Adams felt Cleese’s involvement “would make for quite a stylish moment, particularly if no prior warning is given to the viewers.” This latter suggestion would prove troublesome, although Cleese’s later remarks suggest it may have been pivotal to him accepting the role. Adams promised Cleese that he would not be needed for rehearsals and as a final inducement suggested that if Cleese’s daughter Cynthia was a fan of the show he could arrange for her to “come to the studio and meet some of the monsters – like Tom Baker for instance”.

It’s not known whether Alan Coren was ever approached as Adams suggested for the role that ultimately went to Bron. In a 2001 interview with DWM, Bron later suggested that her involvement would have come about in the usual way for an actor: “Someone says, ‘Are you free?’ and you say, ‘Yes, if the money’s good enough!’” It isn’t known when she and Cleese agreed the roles. Their characters were still referred to as “two Englishmen” in the camera script used for recording, suggesting their casting may have been confirmed late in the day. By the time of the transmission script being typed up (i.e. a script for records purposes that reflected the final version of the programme) they were referred to as “two art lovers” and their dialogue attributed simply to ‘man’ and ‘woman’.

The scene was recorded on 21 May 1979, the story’s first day in studio after the Paris location shoot and (actorless) model filming. The Denise Rene gallery is real but here was realised as a set in BBC Television Centre’s Studio 3. Cleese has not, as far as I can discover, ever commented on his brief connection with Doctor Who, but Bron recalled: “We were in another world that day. We burst into the studio, we quickly rehearsed our single scene, we recorded it – and then we left as if nothing had happened! It was very funny.” She found both Baker and Cleese “very charming.”

Certainly the scene would have been recorded rapidly but, even so, the editing notes indicate that a number of takes were involved. Possibly Bron was there for less time than Cleese as, at some point during the day, he found time to record some comedy skits on the set with Tom Baker, which did not involve Bron. In one, Cleese approaches Baker and asks for an autograph for his blind godson but neither has a pen. Cleese gives the punchline: “Oh, never mind. I’ll tell him you signed it.”

In another, Cleese delivers a large piece of video equipment to Baker in the TARDIS, the cryptic punchline of which is presumably an in-joke for the intended audience. That audience would primarily have been the BBC’s engineering department but also other internal areas, as the sketches were recorded for that year’s ‘Christmas tape’ (named ‘Good King Memorex’) – a compilation of out-takes, improvised sketches and crude humour that was assembled in the BBC videotape department and shown at various festive get-togethers.

As Hayes noted, both Bron and Cleese were keen to keep their appearance a surprise and avoid any advanced publicity. In an interview published by DWM in 1997 long after his death, Graham Williams reported: “I agreed whole-heartedly with John’s concern that he didn’t want it to over-balance and suddenly become ‘The John Cleese Show featuring Tom Baker’. So, at his request and with my agreement, we kept the pre-show publicity down to an absolute minimum.” However, it didn’t prove quite as simple as that.

Rather than use their real names, Cleese and Bron asked to be credited as Kim Bread and Helen Swanetsky respectively. During post production, Willaims wrote to them both to explain that: “a dictate from above has banned the use of pseudonyms in the Radio Times”. Given their reluctance to be credited, Williams proposed simply omitting their roles from the Radio Times listing. However, he still wanted to credit them by their real names on the programme itself, emphasising that these credits would only be seen at the end of the episode (i.e. not giving any advanced notice of the performers’ presence). Williams noted that the alternative was to omit the credit altogether and that: “in the absence of an honour like say, the Croix de Who, the least we can do is credit your sterling efforts!”

Williams concluded his letter asking Cleese and Bron to let him know how they felt about his proposal, a request he may have come to regret. Cleese at least did not feel at all happy about it. He went above Williams’s head to his boss, Graeme McDonald, head of drama Series and Serials, who he understood was the source of the disagreement. Cleese complained: “I was very disappointed to hear today from Graham Williams that you vetoed our little joke about Kim Bread. I don’t think the audience would have been frustrated or disappointed or would have felt themselves unduly misled. I think it would have been a little touch of humour that would not have gone amiss in the huge organisation that is the BBC.” He concluded: “Also the idea amused me and was one of the reasons I agreed to do the show.” Bron’s thoughts, if she expressed any, are not recorded.

McDonald approached Williams for some background information about the ‘Kim Bread’ joke. Williams assured him that there was no reference anywhere in the story to a Kim Bread but that Cleese thought it a “very funny name.” He went on: “Whilst I hesitate to disagree with a comedian of John Cleese’s standing, I must confess that seeing “Kim Bread” appear on the screen would not have me rolling about on the floor – perhaps that is why he is millionaire and I’m a lowly MP6!” The final reference was presumably to his BBC staff grade.

Williams took the bull by the horns to resolve the matter, reassuring McDonald: “I spoke to John and he has agreed to a credit in his own name on screen and no billing in the Radio Times.” As requested there was no publicity given to the casting of Cleese and Bron. According to Hayes on the story’s DVD commentary, once they belatedly learned of this after transmission, “the press were absolutely furious that they hadn’t been notified.”

According to correspondence received by both the Doctor Who production office and the Radio Times, the series’ new, more comedic, direction, exemplified by the Cleese and Bron cameo, was drawing a mixed reaction from viewers.

Under the heading ‘’Dr Who’: flawless or farcical?’, the Radio Times printed contrasting views. Lee Rogers from Hastings included in his praise “the surprise guest appearances by John Cleese and Eleanor Bron”. However, Paul R Maskew of Exeter complained of the ‘deterioration’ of the series. He reported: “The casting of John Cleese and Eleanor Bron as two art gallery visitors was done deliberately to gain laughs which it did – I watched the episode among some 30 or more people. The scene totally distracted people from the story. Is there no end to the continuing ‘joke’ being played upon dedicated Dr Who viewers?”

In response to one criticism, Adams replied to say that City of Death had “provoked an avalanche of correspondence, many people saying the “best ever” and some, such as yourself, saying “worst ever”.” What wasn’t ambiguous, however, were the episode’s ratings. The audience for the story grew steadily across its four episodes from 12.4million until 16.1million watched part four with the Cleese and Bron cameo. It remains the highest rating Doctor Who has ever received. It does have to be acknowledged though that this was helped by the main competition, ITV, being off-air at the time due to strike action, reducing the audience’s choice of viewing.

The episode was the sixteenth most-watched programme of the week on BBC1. This was a significantly higher position than that achieved by other episodes in the same season which also went out during the ITV strike, indicating the serial grew its audience on its own merit. Five days after the broadcast, Cleese was seen on BBC Two in the final episode of Fawlty Towers, Basil the Rat, the completion and transmission of which had been greatly delayed by a strike at the BBC.

Although it is my speculation only, it’s possible that the failure to complete and transmit Fawlty Towers as planned was in part the reason Cleese was reluctant to have his Doctor Who role publicised. He may not have wanted to risk becoming, however briefly, associated with Doctor Who for a cameo role in case this should distract the audience from his starring role in his own creation before it had completed transmission.

City of Death is now regarded by fans as one of Doctor Who’s best, and funniest, stories. When DWM polled its readership for the series’ sixtieth anniversary 2023, City of Death was voted not only their favourite Tom Baker story but their eighth favourite story of the entire series. Most fans seem to appreciate the cameo of Cleese and Bron as a welcome light-hearted interlude in the high drama of the Doctor’s race to save all life on Earth.

Let’s return briefly to the letter Adams sent to the disgruntled viewer. He concluded: “Incidentally, I’m a bit alarmed by your assumptions that thinking and laughing are mutually exclusive activities.” This neatly underlines what the Cleese and Bron scene does. It makes us think and it makes us laugh, and surely that’s a good thing.

Images © BBC

Thanks to David Brunt for a useful correction

Sources

Douglas Adams interview by Charles Martin, Doctor Who Magazine, issue 313, February 2002.

Alan Barnes’s ‘The Fact of Fiction’ feature on City of Death in Doctor Who Magazine, issue 350, December 2004.

Eleanor Bron interview by Benjamin Cook, Doctor Who Magazine, issue 304, May 2001.

Michael Hayes interview by Philip Newman, Doctor Who Magazine, issue 224, April 1995.

Graham Williams interview by Philip Newman, Doctor Who Magazine, issue 251, May 1997.

Sixtieth anniversary poll results in Doctor Who Magazine, issue 597, December 2023.

City of Death production file documentation, Radio Times listings and DVD commentary, included on the Doctor Who: The Collection Season 17 bluray boxed set.

Doctor Who in the Radio Times, seasons 16 & 17, 1978-1980, available here.

‘Good King Memorex’, currently available to view in a slightly sanitised version here.

(In hope more than expectation I did ask John Cleese’s agent if it would be possible to ask Cleese what he recalls of his involvement with Doctor Who but as anticipated there was no response.)