A celebration of Ray Cusick

Last month was the 60th anniversary of Doctor Who and this month it’s the same anniversary for the Daleks. It’s a truism that Doctor Who would not have succeeded without the Daleks. Equally, the Daleks would not have succeeded without the design work of Ray Cusick. Today is the 60th anniversary of the Dalek’s first full appearance in Doctor Who, in the second episode of The Daleks, so now seems a suitable moment to reappraise Cusick’s contribution not just to the Daleks but also to the series more widely.

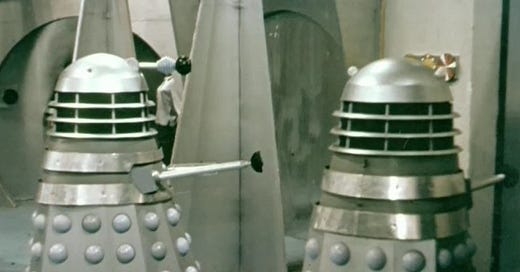

What’s most striking about Cusick’s original 1963 Dalek design is how alien it is, resembling nothing terrestrial at all (there’s no conscious referencing of human man-made objects, as there was in the ‘battleship’ design ethos used in the 2005 redesign, for example). Yet it’s also practical for the job it had to do. Cusick was not designing abstract art but a physical prop which had to be controlled by an operator within. It’s telling of his pragmatic approach that Cusick’s first step was to draw the outline not of the Dalek, but of the person who would operate it, before extending the design from that starting point. That’s why the skirt protrudes further at the front than at the back: space for the operator’s knees.

To me, the design of Dalek seen in their first appearance (often styled a ‘Dead Planet’ Dalek) is not only the original, but also the definitive version. Cusick’s design is sleek and clean, using straight lines, circles and curves, but very few corners or right angles. Its use of simple geometric forms is reminiscent of the futurism and art deco movements of the early 20th century. In the realm of tangible engineering, it seems to share something of the design ethic used in German military equipment of the 1930s and ‘40s, as seen in no end of war films; think of their sleek, almost stylish, machineguns for example.

It’s unlikely that much of this was deliberate on Cusick’s part, but nonetheless his design is remarkable in its use of shapes and lines. Although it has been much modified since, the design has remained recognisable and highly successful as long as its basic lines and shapes remained (ie until the misshapen ‘New Paradigm’ version came along), confirming the genius of Cusick’s original vision.

Whilst it’s obviously the Dalek design that he’ll be remembered for, Cusick’s other contributions to Doctor Who were also of a high calibre. The rest of his design work on The Daleks is particularly noteworthy. Despite Terry Nation’s lack of scripted description, Cusick manages to make the Dalek city interior interesting, with a design that dovetails with that of its inhabitants to create a consistent physical world for the story. He uses rounded-off corners and curves, with low doorways and circular controls, that reflect the design and needs of the Daleks.

The shots of the city’s exterior (which Cusick also oversaw, as he designed not only sets and props but also special effects in these early years) are achieved with a large and greatly detailed model, enhanced with dry-ice mist and sympathetic filming. It’s probably Doctor Who’s best ever model sequence. Another impressive model shot of Cusick’s was the crashed rocket in The Rescue. Cusick’s designs for the rocket interior sets used different angles for the floors of the three separate sections for continuity with the three broken sections of the model rocket.

Inspired by the work of architect Antoni Gaudi, Cusick used curves again in his designs for The Sensorites, almost entirely eschewing right angles and straight lines in his city sets. A further superb miniature was seen in The Chase; the Mechonoids’ art nouveau-styled city on stilts is an inspired design, contrasting with the clinical functionality of the Mechonoids themselves – appropriately so, since the Mechonoids were supposed to be preparing the planet for human habitation.

Even when his work was more pedestrian, Cusick deserves credit for managing so much on budgets famously so small. Look at The Keys of Marinus for example, which demanded five entirely separate groups of sets in the space of six episodes, which Cusick furnished with an impressive economy and creativity (more on this in a few months).

It was sad to see Cusick often looking and sounding so glum when interviewed about his Doctor Who work, though some disappointment and bitterness is understandable given the lack of recompense for his immense contribution to the success of the series. Yet, even if it wasn’t financially rewarding, by designing the Daleks he achieved some sort of immortality, and few television designers have done that.

Images © BBC

This is a revised version of an article originally published in Panic Moon in December 2013